Last weekend I was in Brooklyn and went with my son and daughter-in-law to the campus of Pratt Institute, a college of art and design, for the purposes of a picnic lunch and to stroll its Sculpture Park. (Here’s a link if you want to scroll through part of the collection.) The campus is an oasis of peace and beauty. Back home now, with pictures on my phone, which you’ll surely see in more upcoming blog posts, I landed on some notes I took when reading Mark Doty’s Still Life with Oysters and Lemon years ago.

Still Life is a book-length essay, 67 pages with only space breaks, in which Doty ruminates on a painting he has fallen in love with, "Still Life with Oysters and Lemon" by Jan Davidsz de Heem. Doty begins by setting a scene, a still life, if you will, as he leaves New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art after first seeing the painting. The first paragraph is full of sensory detail: "sharp cracking day", "tailpipes of idling taxis", "rhythmic hurry of wings", "solidity of the museum's columns", "blue and white paper cups of coffee", and more. Later he writes:

"But what I'm feeling today isn't retreat, isn't a silent respite; rather it's as if the generous attention lavished on all these things is calling me toward engagement. Is forty-five the midpoint, the hinge point of life? In the past I have gravitated toward transcendence. I've sought weightlessness, unboundedness, continuity, have followed the wish to be outside of time. I have wanted to escape or deny the body; I have loved art that defies limit, that reaches for a scale beyond the human.

But these paintings fill me with the pleasure of being bound to the material, implicated, part of a community of attention-giving. This is what we do with sight, give it out, give it and give it away in order to be filled. Elisabeth Bishop's travelers 'looked and looked our infant sight away,' and that is what I feel Paul and I are doing today, taking in and taking in, joined to a brethren of the lovers of this world. Who go about their seeing—by lens and by canvas, by microscope and camera obscura, by notebook and daybook—as if it were the most crucial work we could choose."

Doty suggests that the poet and still life painter alike "think through things." Both use things to nurture love—i.e., "tenderness of experience"—toward the world. "We are instructed by the objects that come to speak with us, those material presences. Why should we have been born knowing how to love the world? We require, again and again, these demonstrations."

~~~

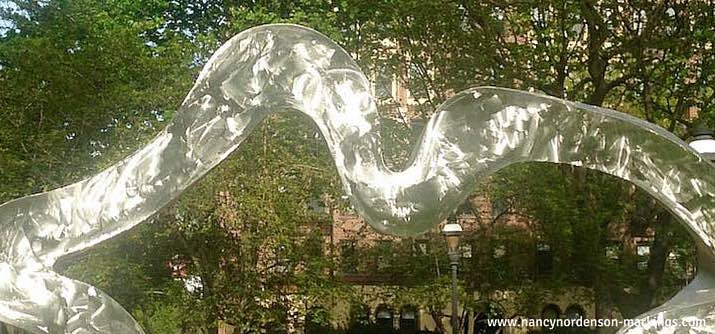

[Photo: taken on a beautiful spring Saturday at the Pratt Institute Sculpture Park in Brooklyn of a piece by Hans Van de Bovenkamp.]