I’ve been reading The Code Breaker by Walter Isaacson (2021). My father gave it to me, and he and I have been talking about it in the evenings on the phone as we go through the book. One small scene towards the beginning of the book has continued to hum in my brain, although it has nothing to do with the work of mapping the structure of RNA, the theme of the book. In reality, however, this small scene has everything to do with that work, which means it has everything to do with the fact that we now have a Covid vaccine.

Jennifer Doudna, PhD, the subject of the book, and her colleague, Emmanuelle Charpentier, PhD, won the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their invention of an RNA-guided gene-editing tool, which played a key role in the development of the Covid vaccine. The scene I’m thinking of was when Doudna was in sixth grade, and her father gave her a copy of The Double Helix by James Watson, a book that detailed the discovery of the structure of DNA. Reading that book was a pivot point for Doudna. While it didn’t give an immediate 180-degree shift in whatever her sixth-grade self was doing or aiming at, the shift carried her somewhere.

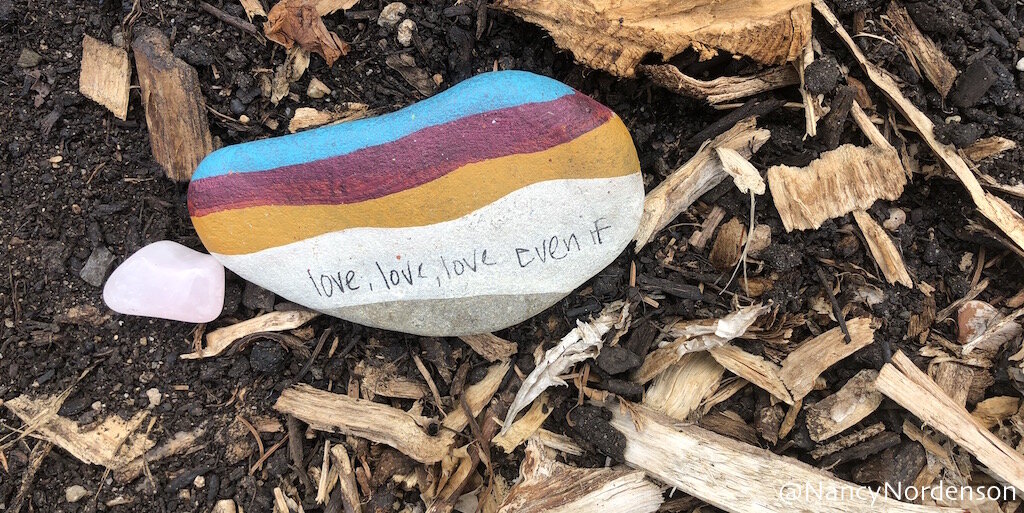

The trajectory of any subtle pivot, carried over many years, changes everything. Take a piece of paper and draw a dot on the left side of the paper and another dot on the right side. Now draw a line between the dots. Next, draw a third dot just a tiny bit above the dot on the right side. Finally, draw a line between the original left dot and the new right dot. Imagine that the lines go on and on beyond the page, and think about how those two lines would travel out across time with the distance between them growing. It makes for an interesting assignment: think back to childhood, or later, and consider what was the toy, the book, the conversation, the game, the film, the scene that nudged you ever so slightly or is nudging you even now.