Back in March I listened to Zoom episodes of the Madeleine L’Engle Seminar “Poetry, Science and the Imagination,” produced by Image and hosted by Brian Volck, every Wednesday over the lunch hour. All five episodes were wonderful, but I was particularly intrigued with Mary Peelen. A science-minded writer, although not a scientist, Peelen has written a book of poems called Quantum Heresies, which I ordered soon after the episode. Her poems are loaded with reflections on chaos theory, parabolic arcs, chromosomes, supernovas, gravity, algebraic variables, and a myriad of other images that become metaphors for life.

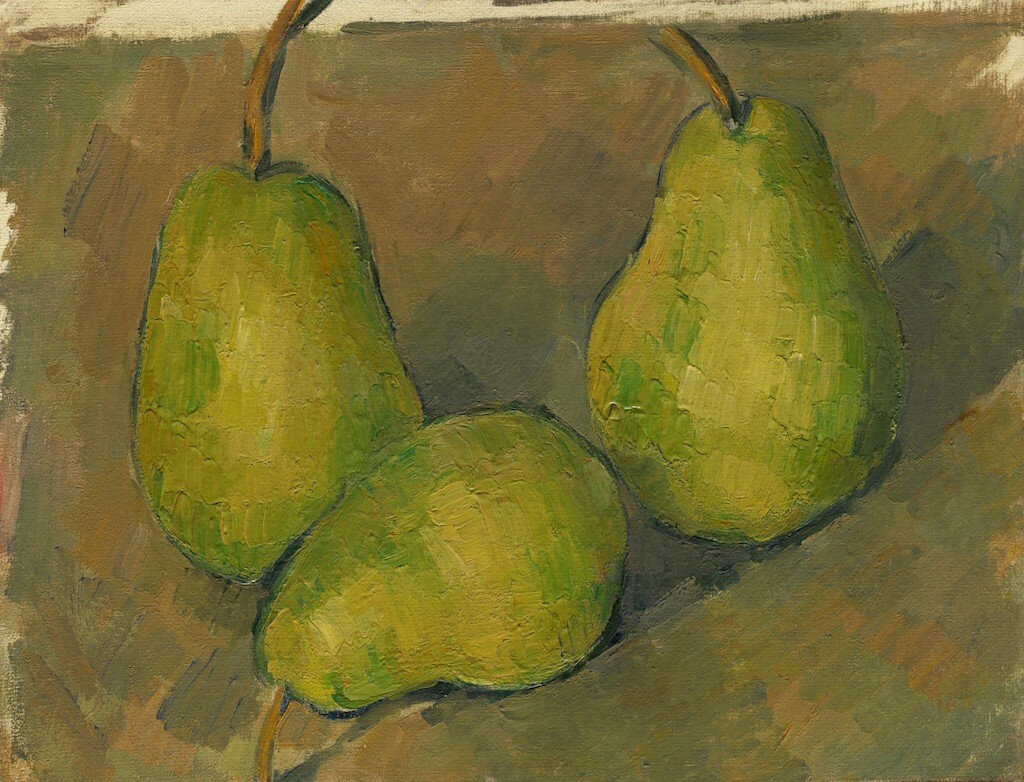

In the poem titled “One,” she writes of a pear. An ordinary pear.

When I come to you

offering one small green pear,

I’m asking you to believe in

every green there is,

at every hour.

The whole tree.

This past year we’ve been eating a lot of pears and until reading this poem I never once thought about the trees from which they came. Do I even know what a pear tree looks like? In what town did the trees grow? What state? What did the field of pear trees look like? Each pear existed and grew on a specific branch on a specific whole tree in a specific location under a specific square of sky and was picked by a specific set of human hands belonging to a specific person and packed into a specific box before being loaded onto a specific truck and on and on before it finally arrived at my house and was bitten into by me.

The thought exercise may seem inconsequential, but it does open up a point of wonder, a point of connection to a world beyond my appetite, my refrigerator, my grocery store. Multiply this exercise by all the different things you eat during the day—an egg, an onion, a steak perhaps—and the world rapidly expands yet keeps one in a web of provision.

Two small green pears are now sitting on my kitchen counter. While waiting for them to soften a bit before eating, I’m wondering where they’ve been.

~~~

[Photo: “Three Pears” by Paul Cézanne; copyright free via the National Gallery of Art]