A little over a week ago I watched the new documentary about Fred Rogers, Won’t You Be My Neighbor? Have you seen it? I have fond memories of my sons calmly and happily watching Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood on television when they were little, and while I have always been grateful for Fred Rogers, I was ever more so after watching the documentary.

I’ve been thinking since about how Fred Rogers became who he was and what he has to say to us, even us grown-ups, about who we become. From all that was shared in the documentary, two things, in particular, stand out.

The first is that he was a minister with a degree from Pittsburgh Theological Seminary. He worked in television before going to seminary and after he graduated from seminary. He knew that being a minister was not limited to standing behind a pulpit, as valuable as that definition of minister is. A man or woman who has prepared to serve God, or intends to serve God whether or not a degree is behind that intention, can do so in a multitude of ways.

The second is what he had to say to all of us, even and especially us grown-ups, about what we do with our lives. In a special television appearance after 9/11, he challenged his listeners to be about something big:

“No matter what our particular job, especially in our world today, we all are called to be tikkun olam, repairers of creation. Thank you for whatever you do, wherever you are, to bring joy and life and hope and faith and pardon and love to your neighbor and to yourself.”

Read that phrase again: Repairers of creation.

Today with the strong, and sometimes misguided, emphasis on finding one’s unique vocation or “call” and following only that perceived path, this reminder that each of us is to be about the mending of creation by bringing joy, life, hope, faith, pardon, and love to the world around us no matter our job—in any job, in every job—is so needed.

If you haven’t seen the documentary, maybe you can still catch it in a theater. If not, for about the cost of a hamburger or large latte you can watch it on iTunes or another online service. I do hope you will.

~~~

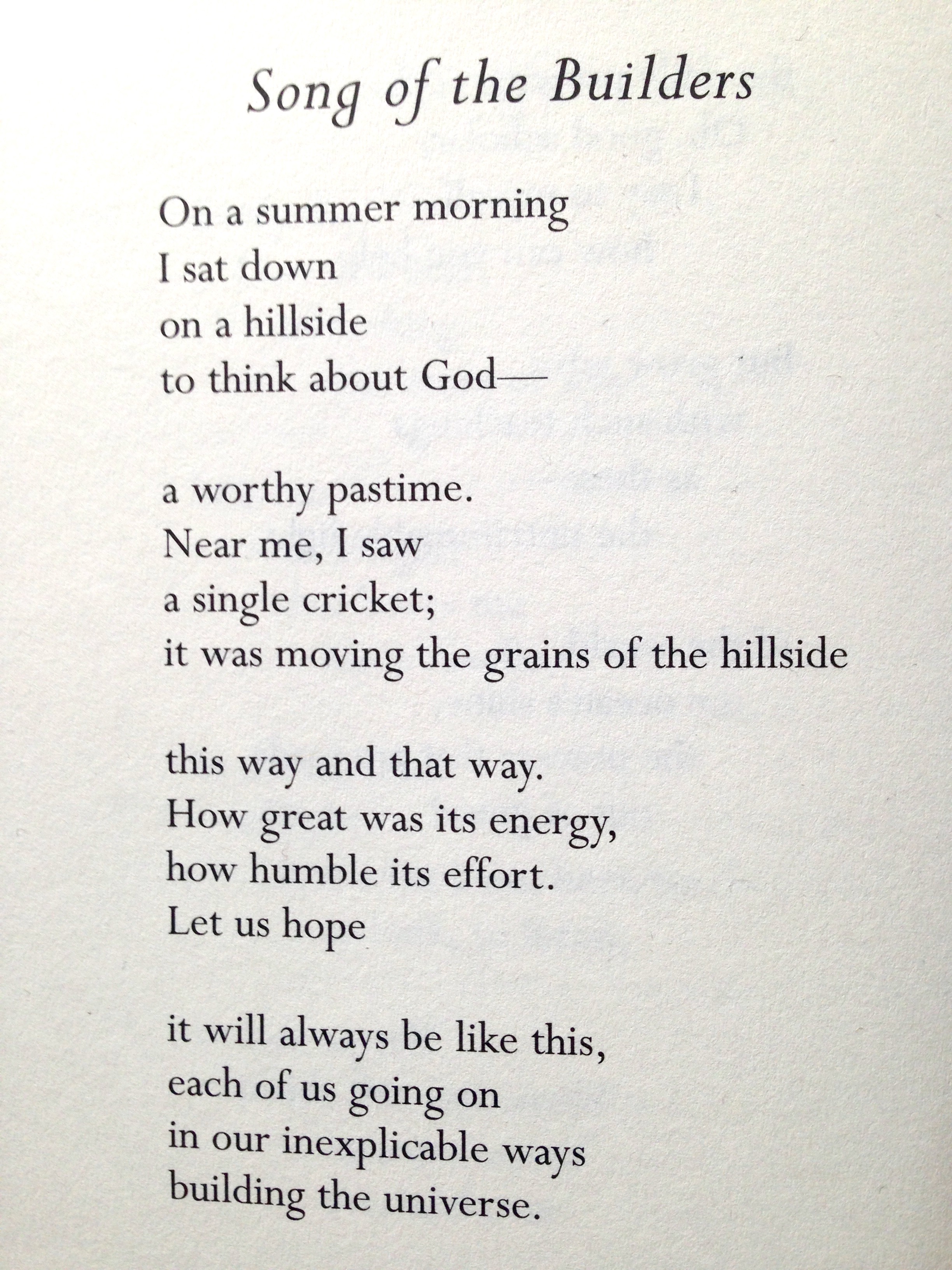

[photo: taken on a recent autumn walk]