I want to spread the word about a tremendous milestone for a wonderful journal. The 20th Anniversary issue of IMAGE (Art, Faith, Mystery) will soon be available on bookstore shelves and mailed to subscribers. Included are contributions by Kathleen Norris, Ron Austin, Robert Cording, Thomas Lynch, Stanley Hauerwas, Valerie Sayers, Makoto Fujimura, Tim Hawkinson, Mary McCleary, Joel Sheesley, Roger Wagner, Ruth Weisberg, Theodore L. Prescott, Wayne Adams, Alfonse Borysewicz, Catherine Prescott, James Romaine, Ron Hansen, Scott Cairns, Franz Wright, Sam Phillips, and more. New subscribers will get this issue FREE. Click here for more info. I've been a subscriber for about four or five years and just renewed so as not to miss an issue, this one in particular.

Surviving

The last several months I've been immersed in a six-part project on cancer therapy, a topic that is at once bleak and exciting. Targeted agents in development and genetic profiling for individualized treatment suggest a future of increasingly hopeful outcomes. Nevertheless, the million dollar question for people who receive a diagnosis of aggressive malignancy remains, How long have I got?

Clinical trials in these settings typically use median survival--overall survival or progression-free survival--as the measuring post by which to compare one treatment regimen to another or to placebo or observation. To review statistics 101, the "median" number in a series of numbers is the middle value, with half the numbers above and half the numbers below. For example, if 32 apples are distributed among 7 children, with one child receiving one apple, three children receiving four, two receiving five, and one receiving ten, the median number of apples is four. An understanding of median is important in thinking about survival data because the upper and lower range of numbers in the series doesn't change the median. If instead of 10 apples, the last child in the example above received 1,000 apples, the median would still be four. (In contrast, mean is the average of all the numbers in the series and mode is the most common). In cancer terms, if the median survival is one year, the survival for some is a few months, and for others, many years.

For Christmas 2007, my son gave me a book of essays by Harvard professor and evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould called The Richness of Life (great title!). One of the essays, "The Median Is Not the Message," is about the hope inherent in statistics, contrary to popular belief. In 1982, Gould was diagnosed with abdominal mesothelioma, a particularly aggressive form of cancer with a median survival of eight months. He read everything he could about cancer, this cancer, and survival statistics. Once he realized, with relief, the extended possibility of survival beyond the median, he knew he had time to "think, plan, and fight." He flung his efforts into increasing his odds of landing at the far end of the survival range, which he succeeded in doing, living for 20 more years.

His essay explains in very understandable terms the good news he found through his analysis of statistics. It's worth a read if you have cancer, know someone with cancer, are afraid of cancer, or just want to have some practice looking at a negative situation from a positive point of view. You can find the essay in the anthology I mentioned or on numerous cancer advocacy sites, including here.

It is the day before New Year's Eve and so a more appropriate post on this day might be a hip-hooray for the fresh start ahead, or a musing on how the changing economy colors the outlook for the coming year, or even a preview of what I'll be serving guests as the clock strikes midnight. But I'll stay with this post anyway. After all, what better time to focus on the who-knows-what-is-possible streaming flare of life than hours before a new year begins.

~~~

Figure source: http://www.stat.psu.edu/online/development/stat500/lesson02/lesson02_02.html

New on the stack

Three new books are on my reading stack. Rather than wait until I readthem, I wanted to post something about them now, particularly because all three were written by friends of mine. Below are excerpts from their beginnings and something about the book and/or author.

The Lost Daughters of China: Adopted Girls, Their Journey to America, and the Search for a Missing Past

"In the Pearl River Delta of southern China, the land is criss-crossed by water. Rivers, like long fingers, reach deep into the landscape from the South China Sea, and along their banks fertile soil would seem to promise paradise. The climate is subtropical and mild, rainfall is plentiful, and the fields are patchworked in muted tones of green. Farmers tend their rice in rolling terraces. Water buffalo stand placidly in the fields. Where there aren't rice paddies, plots of elephant-leafed taro and pole beans spring from the ground. Sugarcane grows in profusion, and there are mulberry trees, harboring billions of silkworms...."

This book is a revised edition of the original 2000 National Bestseller. Evans has updated it to include information about cultural and political changes in China since she first adopted her daughters, and also to include insights into the lives of adopted girls as they are growing up in the United States.

Karin Evans is a lovely lovely (should I say it again for even greater emphasis?) woman. I had the privilege of getting to know her when we were both recent students in the Seattle Pacific University MFA program.

Original Faith: What Your Life is Trying to Tell You

"Love occupies a special place in the realm of human feelings. We identify it closely with human beings at their best, and this is so whether we view ourselves as secular or religious. Love never really goes out of fashion. It is a perennial source of trouble to cynics. Whatever we may believe or not believe, our love, as the song says, is here to stay...."

Paul Martin and I first "met" via correspondence on his original blog some years ago. His current blog, named for the title of his book, is a place of lively and respectful spiritual dialog. Earlier this year, he applied his gracious conversational skills to an interview with me.

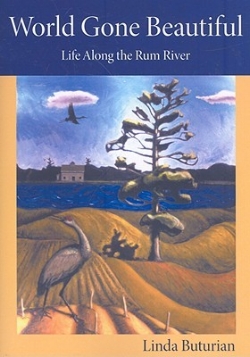

World Gone Beautiful: Life Along the Rum River

"When you drive down County Road 4 in Bogus Brook Township, turn onto a tree-lined gravel road marked by a yellow Dead End sign. If you are in a dark or speculative mood you might interpret that sign as a message about our lives (or your own). Keep going, past the black and white Holsteins taking shade under the poplars. If the neighbor hasn't just spread liquid manure on his field, roll down your windows to get a glimpse of the wild pink geraniums blooming in the ditch, and to hear the frogs before they cease all at once as you pass their marsh, and pick up again only when you are driving along the cornfields..."

I met Linda Buturian last summer at the Glen Workshop in Santa Fe, but she lives outside of Minneapolis (along the Rum River) and teaches at the University of Minnesota. After meeting her and finding out about her book, I went to her reading at Magers & Quinn, one of the few independent bookstores still in existence, and laughed and laughed. The section she read was at once profound and very funny.

Coffee or tea and what starts a day

Some mornings are coffee mornings and some are tea mornings. The choice is somewhat dependent on what kind of coffee or tea we have in the house, and if a carton of half-and-half is in the refrigerator or not, but often it’s just mood. Generally, tea is a nurturing sort of morning; coffee, a let’s-get-going sort. Today tea is sitting beside me, sweetened with raw honey supposedly rich with enzymes. The propolis from the honey jar mounds up on the side as I dig for the smooth honey underneath. It would be interesting to track the average trajectory of days that start with tea and compare it with the average trajectory of days that start with coffee and make a study of it. But what would be the control? A day that starts with water? And how many days must one track in order to have a valid comparison? And how to rule out confounding factors, like the sound sleep of one night versus the turn and toss of another? Little of what comprises the start of a day can be isolated and measured.

In college chemistry I did a project of extracting caffeine from equivalent amounts of brewed coffee and tea and then comparing the extracted quantities. If I remember right, the results from one of the beverages was not as expected, and therefore, the study bore repeating. Somewhere in my basement is a box labeled "College," which holds, among other things, a lab notebook that I loved with a blue cloth cover and pale green grided pages. Somewhere on those pages are the details of the two mounds of white powder, their method of isolation and respective quantities. Nowhere on those pages, however, is the pleasure from either coffee or tea calculated, dissected, or otherwise explained.

From Virginia Woolf's, Between the Acts:

“She took the little silver cream jug and let the smooth fluid curl luxuriously into her coffee, to which she added a shovel full of brown sugar candy. Sensuously, rhythmically, she stirred the mixture round and round...She looked before she drank. Looking was part of drinking. Why waste sensation, she seemed to ask, why waste a single drop that can be pressed out of this ripe, this melting, this adorable world? Then she drank.”

Subliminal hope

I had a doctor's appointment this week. On the desk in the examination room, replacing the usual stack of women's and news magazines, was a stack of materials on stress management. Everyone's all knotted up these days was my doctor's observation.

Listening to the evening news or even the news that comes across my telephone some days it's easy to imagine danger threatening at every corner. Safety nets irreparably ripped. It's easy to yield to the impulse of setting one's face like flint against the risk of need or frailty or disappointment, determining to be one's own safety net; work every minute and save every dime against the hour of need; take every precaution about one's health; why did we stop building backyard bomb shelters anyway? And the stomach churns and the heart pounds and life darkens.

Calm; calm.

This past summer I bought a Psalter, which is just a bound copy of the Old Testament Psalms. In this Eastern Orthodox version, the Psalms are broken down into 20 sections called "kathisma." A schedule in the back of the book suggests the entire Psalms be read through weekly, with three kathisma read each day and two on Sunday. Although I bought the book because I wanted to develop a habit of reading through the Psalms, I hadn't anticipated quite this rigorous a schedule. Despite an initial attempt to keep to this standard, I fell into a more leisurely routine of one kathisma daily. Doing this for a couple months now I'm starting to understand the beauty of the weekly goal, even of my schedule-lite.

So many lines of Psalms going into the brain each day realigns one's thoughts. These are not just aphorisms or reminders of truth or points of study to underline or outline in a notebook, but curative corrective therapy. A primer on reality: the nature of the world and the glory of God, the match between the longing for hope and hope's source.

Reading so many lines everyday it's impossible to concentrate on each and that's okay. Good in fact. The lines slip in and do their work. Nothing is wasted. I can imagine that the lines that do get my attention, that do call my thoughts back from their wandering are the ones needed now like an aspirin--or a tranquilizer--whereas the others are more like a multivitamin, strengthening for days ahead.

There's this: "Work in me a sign unto good." And this: "Under His wings shalt thou have hope." And this: "All things wait on Thee." And finally: "The Lord is well pleased in them...that hope in His mercy."

Bells: Listen, read

The fall issue of Desert Call, just out, includes my essay "Waves and Oscillations." I feel compelled now to say what the essay is about, but at this point I get stuck. I could say it's about the theme of the issue, "On Holy Ground." I could say it's about church bells, or churches, or prayer, or failure, or expectation, or the call and work of the Spirit, or being known, or mercy, or the power of simple kindness. Alternatively, to quote Flannery O'Connor, "When anybody asks what a story is about, the only proper thing is to tell him to read the story."

Pick a day, any day

While I was in Santa Fe a couple weeks ago I re-read Annie Dillard's, Holy the Firm. She got her title from the name of a substance ("Holy the Firm") that is deep deep down in the "waxy deepness of planets" that some claim is "in contact with the Absolute, at base." Reading that, I couldn't quite get my brain around what such a substance would be, and where, and how it had been either imagined or ascertained in the first place. While reading, however, I was sitting on a balcony within sight of the Sangre de Christo mountains, and glancing from page to blood-red rock I had no trouble at all comprehending what I could easily label Holy the Firm.

Dillard wrote the book based on the happenings of three consecutive days, with each of the three chapters representing a day. I think I read somewhere that she made a deal with herself to write about whatever happens in the next three days, but I may be remembering wrong. It seems more likely that a certain three days passed, and those days had alerted her in such a way that she knew she would write about them. I say that because at least one extraordinary thing happened in those three days around which a substantial work could grow. I say that because her three-day set was vastly more evocative than my average three-day set.

Nevertheless, I want to cheer for the first scenario: that she rolled the dice of days and these were the three that went face up. I want to believe--and do believe--that with wide enough eyes and an imagination to match you could take any moment or set of moments and link it forward in time or back, or hook what fills that moment, whether living or inanimate, with anything else past or present, with nearly infinite possibilities. I've been trying to think of a way to describe the potential for infinite linking possibility in geometric terms, but the same brain that is having trouble grasping that deep waxy planetary substance is also having trouble remembering the ninth-grade geometry Mrs. Runkle taught me. Therefore, I'll dispense with the X, Y, and rotating Z-axis I've been mentally playing around with and limit myself to a simple sphere, with any particular moment or set of moments as a seed at its core. The sphere is Everything and any plane that cuts through its diameter, by definition, cuts through its core. Voila! An inelegant proof that any finite Something can be extrapolated and linked to the point of nearly endless possibility on the page. Might it even connect with the Absolute?